Returning to stage writing seven years after the success of The Ferryman, Jez Butterworth’s The Hills of California seizes upon aesthetic and experiential possibilities particular to theatre. The play unfolds slowly at first, taking its time to draw out its central situation while building atmosphere from an out-of-tune piano (at first heard from offstage), the labyrinthine corridors of the hotel, and the inescapable blazing heat of 1976’s famously scorching summer. As the play unspools, we learn of the four Webb sisters, raised in the hotel their mother ran, a mother who now lies dying upstairs from stomach cancer, for whom each sister feels a complicated mixture of fear and admiration.

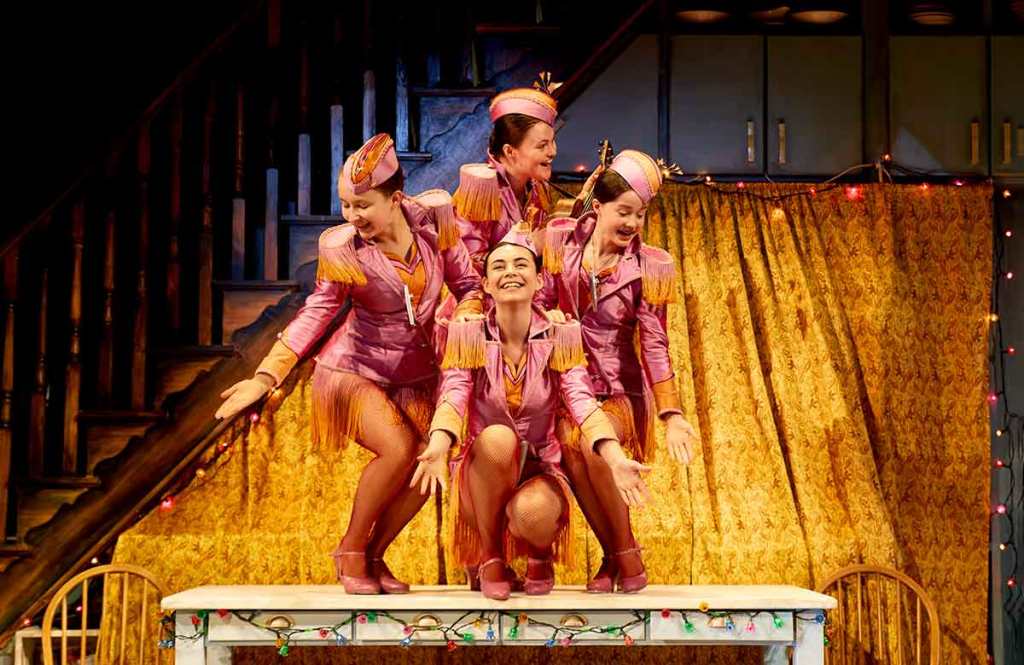

Set across two timeframes, at points the play (and Mendes’ staging) has the feel of a Tennessee Williams ‘memory play’. The first act sets the board in both periods, as three of the four Webb sisters convene in the hotel’s stifling parlour, while in the 1950s their younger iterations practice vocal numbers under the imperious glare of their ambitious mother, Veronica. She longs for the girls to be a singing troupe in the vein of the Andrews sisters, attempting through sheer force of will and boundless dedication to push them towards stardom. Butterworth gives enough details (including many references to the now-American-dwelling eldest sister Joan, compared to the England-based others) for an audience to piece together the likely acrimonious dissolution of their group in advance, but the full details are withheld until the end of the hammer-blow second act, when an American agent comes to watch the sisters perform.

The play continues Butterworth’s interest in cultural mythology, and with this comes a pervasive sense of futility and decline. The 1976 Blackpool setting entails a curious double-fold nostalgia; the characters constantly look back to the 1950s – where their dreams of the sisters’ musical quartet died – while some audience members will be able to look back over the 48-year gap between 1976 and the present moment. The rise and fall of Blackpool as a destination du jour is conjured through the genealogy of increasingly and then decreasingly auspicious names that the ‘Sea View’ hotel (and, formerly, spa) has had over the years. Though, as a nurse wryly notes in the first scene, the name is a lie; you cannot actually see the sea from anywhere in the hotel. Their glamorous aspirations have always been built on sand.

The effect is ‘state of the nation’ in an unemphatic sense. Parallels to the present are glancing and for the audience to construct: the devastating effects of high cost-of-living on hospitality settings and culture, the dangers of ultra-hot British summers (which the climate crisis has caused with ever-increasing regularity), and the shuttering of regional theatres. By 1976, the play tells us, over fifty theatres in Blackpool have closed, leaving a mere four. With the family’s matriarch dying upstairs, the effect is a family (and nation) unmoored. Where Butterworth’s 2009 play Jerusalem partially buys into Johnny ‘Rooster’ Byron’s mythologised orientation to England and its landscape, The Hills of California works to deconstruct the hollowness of myths of showbusiness and glamour – bound up in the bathetic invocations of America throughout.

There is a recurring focus on materiality: the talent agent talks of Nat King Cole’s twenty-thousand-a-night fee; Joe is always behind on his rent; the B&B is entering a financial black hole. Yet despite this, The Hills of California articulates a somewhat contradictory theme always lurking in Butterworth’s writing – that our identity is the sum of the stories we tell. The thorny, restless third act mulls approaches of victimhood ambivalently. Joan wears her history lightly, though we are left to wonder how much she has moved on and how much she has simply alienated herself from her life and its past events. Meanwhile, victimisation weighs heavily on Gloria. As Joan says, Gloria’s ‘story’ is ‘a song she’s sung every night, for years, as she drifts off’. The play seems to argue that performance is not simply artifice; it steadily remoulds us over time.

Whether Joan does or does not eventually return is (I think) a substantial spoiler, but one I will discuss as it seems core to the play’s dramaturgy. Butterworth generates tension during the first two acts over Joan’s potential return, and we are left to wonder what kind of play we are in – an Ibsen- or Pinter-esque play of dramatic return, or whether Joan is more of a Godot figure, whose absence only serves to underscore the normality of the other sisters’ lives. The siblings even bet on whether Joan will turn up; second-eldest Gloria either disbelieves Joan’s claim to have had her flight delayed or reads it as a divinely inspired metaphor for Joan’s distant remove from the family circle. Yet Joan does eventually return, near the start of Act Three, played by Laura Donnelly – the same actor who plays the mother – and this moment, set to The Rolling Stones track ‘Gimme Shelter’ oozes with subtly stylish direction. The hotel’s rusty jukebox cranks into gear semi-magically (after previously resisting fixing), and the set spins. It is as if Joan has breathed life into a house preoccupied with death.

However, Joan surprises in her interactions with her siblings. Expecting hostility, she adopts a disarmingly laissez-faire detachment, rising to no barbs and treating sibling Ruby’s almost-fannish excitement at her return with the polite coolness of a celebrity declining an autograph. Joan knowingly asks if they have ‘elected a scapegoat’ – aware that she has been playing this function for the sisters while en route (and in the years before). Donnelly is extraordinary in both roles here, first as a portrait of Veronica’s cracked ambition, and later as the unpredictable, entertaining, difficult eldest daughter.

She is matched by uniformly strong cast, notably including Leanne Best’s ferocious Gloria, who begins the play as a waspishly comic figure, almost coming to blows when Ruby reveals her journey has been pleasant in her air-conditioned car, compared to Gloria’s nine hours of gridlock in an oven on wheels. By the end, Best mines an impeccable tenderness in the fleeting, charged moments of empathy Butterworth coaxes from his characters.

I am in two minds about the structural mechanics of the third act, which creak a little beneath the atmospheric haze of cigarette smoke and glamour ushered in by Joan’s arrival. In the third act, the characters are not quite where we left them, with two interactions revealed to have happened offstage. Firstly, Jillian tells Joan that Veronica confessed to her two weeks earlier. Jillian has then, in between Act Two and Three, divulged the talent agent’s abuse to her siblings, meaning the scene of revelation we expect is substituted with something quite different – though no less emotionally charged. This is perhaps typical of a play in which Butterworth resists staging the more obvious moral dialectics generated by the plot. For example, little debate is expended on the ethics of euthanising their mother to alleviate her pain. Meanwhile, Joan resists rising to Gloria’s taunts and jibes, responding off-handedly and forestalling many potentially debates over conflicting values or actions. Instead, The Hills of California dwells on the emotional consequences.

The arrival of a baby into the plot, who has been (a little conveniently) left outside and gone completely unnoticed by Ruby, further knocks our expectations. The results are palpably emotional, such as in a brief subsequent reconciliation of Joan and Gloria, and Joan tells a delightful story of meeting the two living Andrews sisters when delivering pizza (her musical career having ground to a halt). The play crystallises in its final moments, and Butterworth’s use of a closing musical number (‘Dream a Little Dream of Me’) for me evoked the effect of Lucy Kirkwood’s dance sequence in The Children (2016). In both plays, characters who seem almost hopelessly disarrayed from each other find momentary unity, unity which contains an image of potential future cooperation.

At the core of the play are partial, semi-successful attempts at revivification. Gloria’s husband (Shaun Dooley, gruffly entertaining as characters in both time periods) fiddles with an old jukebox in the hope of bringing it back to musical life. In the final scene, Joan’s return feels set to curdle at any moment, but the presence of her baby snaps them into a sudden sense of collective purpose. In that moment, they reorientate themselves towards the future; all is not lost. The final song suggests a partial reconciliation with the past (and each other), meaning that a more positive future is possible. The play remains ambivalent though. Despite the hopefulness, there is a tacit acceptance that, for all Joan’s proclamations about wanting to get back on her feet, she may never come back.