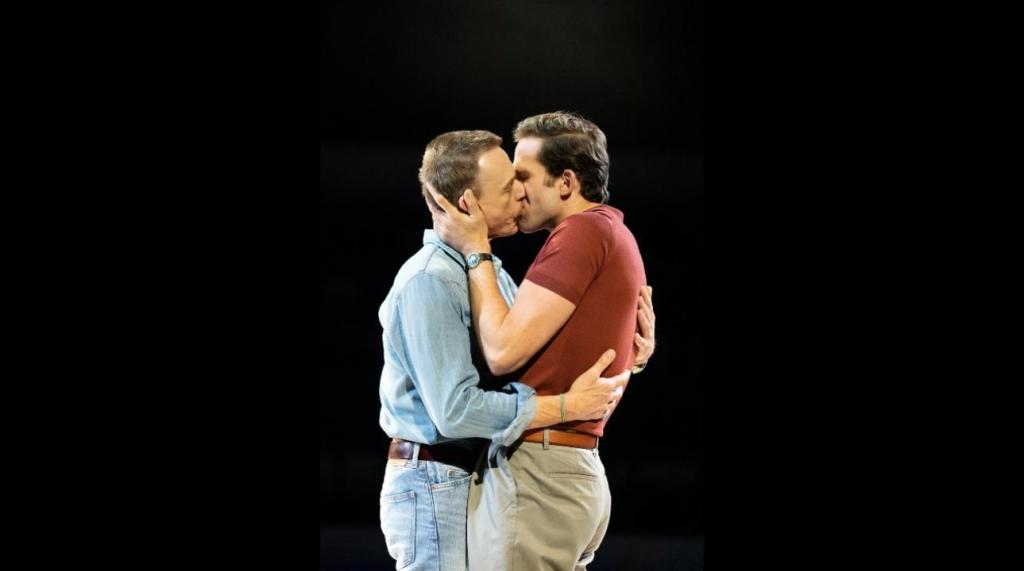

Ian Porter and Arthur Darvill in Rare Earth Mettle

I sometimes wonder how much – during the creation of a play – writers try to anticipate the ways parts of their works could be used against them. Some titles, for instance, are ripe with potential for cruel puns in dismissive headlines. In the case of Rare Earth Mettle, I was struck by the relative danger of setting a significant portion of the play within a scrapyard, filled with rusting trains. As invitations for a dissenting critics go, ‘train-wreck’ is an absolute sitter.

The play is not a train-wreck. In fact, it shines with dazzling wordplay, dizzying ideas and modern art installation-like spectacle (in a good way). Yet it feels almost impossible, and certainly critically insufficient, to examine Rare Earth Mettle’s dramatic strengths and shortcomings without addressing the alarming failures and institutional racism that marked its development, programming and staging.

It is undeniable that the process that led to this play appearing on the stage constituted a failure of stewardship and artistry, as well as actions whose results were racist. According to the Royal Court’s own timeline (published on 18th November in a ‘events and actions status update’), on 5th November, the theatre was ‘notified by members of the Jewish community that the use of this Ashkenazi Jewish name for a ‘Silicon Valley billionaire and CEO’ […] ‘on a mission to save the world’ […] ‘and make millions of dollars in the process’ – risked perpetuating antisemitic tropes.’ The character in question had been called Hershel Fink – now renamed by writer Al Smith to Henry Finn. The theatre has since committed to further antiracism work and does seem to be engaging seriously with the errors that have been made. Yet arguably most alarming in the statement is the admission that the issue had been raised by a Jewish director, in a workshop in September 2021, but ‘this was not taken further, nor passed on to the writer.’ An internal review is underway, ‘to interrogate how this happened across all areas of the organisation’ and how it went ‘unchecked and unchanged.’

The fact that this did go ‘unchecked and unchanged’ is even more striking when the play’s rocky journey to the stage is considered. Originally programmed for April 2020, Rare Earth Mettle had begun rehearsals – with a half-different cast – when lockdown began. It would be rather unreasonable to expect the theatre to have spent the intervening 18 months expending much time and resources on an ostensibly finished play (especially during such a difficult time for shuttered theatres). Yet the additional time makes the fundamental lack of reflection seem even more baffling. That it went through pre-production twice should have provided greater perspective, and at least allowed the artists involved to return to it with fresh eyes. Indeed, the play has clearly been updated – peppered as it now is with references to Coronavirus, now set during the second quarter of 2020.

Reflecting on Rare Earth Mettle, I think that its major problems (the antisemitic connotations being foremost among them) can be attributed to a failure of dramaturgy. This is to say, the development, testing out and analysing the play was subject to before being announced (let alone staged) was insufficient. Dramaturgy should be an antiracist process. It is all about helping a writer say exactly what they want to say. Watching Rare Earth Mettle on stage, some might conclude that the intentions were not antisemitic – yet not only is the effect of racism on its victims far more important than intentionality, but dramaturgy is all about interrogating every aspect of a work and considering its effects on an audience. Good dramaturgy is about serving the ideas of the writer – and making their play’s effect line up with their intentions. Strenuous dramaturgical processes should have raised and questioned the antisemitic effect of the name choice, combined with Finn’s characterisation.

This is also not to say that the problem could have simply been solved by greater time and thinking, but instead dramaturgy should be sure to represent communities more widely. Arguably, this incident ultimately reveals a failure of Jewish representation among those who developed the play.

Critics’ responses to the play have largely ranged from muted to negative. Unsurprisingly, no one wants to endorse a racist play (though some have taken it upon themselves to proclaim it racism-free, just bad drama). Just as I have spent over 500 words summarising and commenting on the antisemitic naming of its central character, so too have critics’ reviews filled up their wordcounts with handwringing discomfort. Yet the result is that the play will receive less critical attention than it otherwise might. This might just be swept away, kept as an uncomfortable footnote in an otherwise auspicious history for the Royal Court. I found it hard to agree with the barrage of one- and two-star reviews – though it is sprawling, has surprisingly rough edges for a play so long in the making, and it is extremely difficult to forget the original name choice for Henry Finn.

In the Royal Court there is a sense of pained embarrassment in the air – not in the actors’ performances themselves, but certainly in the brief, singular bow given by the cast before they disappeared backstage, despite the audience’s continued applause. The shop is empty of scripts of Rare Earth Mettle, normally sold for £4 in the place of a programme. The entire lot have been pulped and will be reprinted with the name ‘Henry Finn’ instead (but only, seemingly, by mid-January, after the run has finished). Perhaps it was an atypical evening, but at the performance I saw (which was not press night), a striking number of people in the (relatively sparse) audience had notebooks with them. Though I am sure they all had various reasons for note-taking, it gave many audience members an appearance of journalistic neutrality – as if their watching the play constituted no endorsement, and that they were duty-bound to note their findings for later report.

So, we return to the trains that open the play – in a Bolivian train cemetery, on top of a salt flat that contains 70% of the world’s lithium. The trains are rusting relics of empire – built by the British to aid the extraction of silver from the Bolivian mountains, through processes that have harmed the natural environment and led to an epidemic of blood cancer in the local area. In one of them lives Kimsa, a local who cares for his dying daughter (who has the cancer that afflicts so many) in one of the old carriages. British and American interest in the land beneath his feet will potentially evict him from his home. Thus, Rare Earth Mettle tells a new, old story of western meddling, colonialism, ecological damage, and disputes over access to minerals. It is oddly paced play – its relatively short first half taking far too long to introduce any moral weight, while the second half is overstuffed. Here too is where more rigorous dramaturgy would have significantly improved the play.

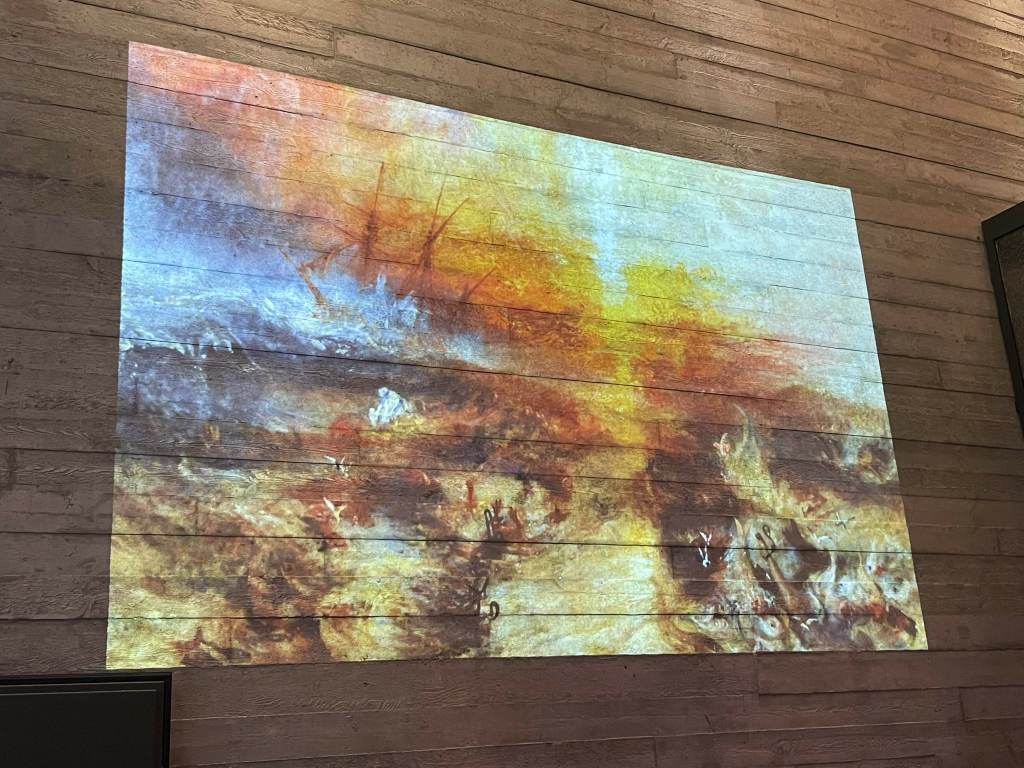

Among the play’s successes, I would count Moi Tran’s set – though it may sharply divide audiences. A checked white floor (somewhere between graph paper and bathroom tiles) is filled with cut-outs, which are wheeled in and out as required. It frequently resembles a high-concept installation piece, with a giant sand (or perhaps salt) timer appearing above the stage, moving back and forth like a pendulum at the beginning and end – perhaps ticking down towards our climate crisis-driven doom. At another the design resembles something by Damien Hirst, a glass box descending from above – filled with occasionally twitching rats. I personally loved the look, especially the dazzling three-dimensional projections that seemed genuinely innovative, but it’s surely a marmite aesthetic. The modular elements also make you feel the length of scene changes – quirky, hypnotic music and robotic dancing accompanying them. In a play so long, some of these moments felt a little redundant.

As for the main characters themselves, Henry Finn – played with arrogant aplomb by Arthur Darvill – is a preening narcissist, though written as a too-bland approximation of Elon Musk. In light of this, the original name choice seems all the more baffling; Musk is not Jewish. By the time we get to the end though, his character has not developed at all. In fact, Smith chooses to double down on the characterisation of Finn as completely emotionally detached. It is Henry’s defining characteristic. Perhaps it is an accurate portrayal of a billionaire, but it is not the most dramatically engaging choice. Henry wants the lithium to power batteries for his new electric car. Smith gives him the slightest touch of benevolence; his determination to sell the car for $35,000, rather than the ‘aspirational’ price of $100,000 is driven by his belief that eco-consciousness should not only be for the wealthy. Still, he remains a billionaire and seeks to profit hugely from the sale.

Genevieve O’Reilly is understatedly brilliant as his nemesis (of sorts) – an NHS doctor called Anna who wants the lithium for a plan that is, at best, a moonshot. O’Reilly contends well with the odd clunky line and almost convinces in her explanation that she wants to introduce lithium to the British water supply – thus giving everyone better, stabler mental health and improving quality of life, especially in poorer areas of the UK. Her trial in Stockport is, to her, a huge success, yet Smith cannily uses the pandemic to trash the study’s verifiability. Of course mental health A&E presentations were down, another scientist tells her; there’s a pandemic so A&E presentations were lower in general. Anna does not stop for a moment to consider social factors for Stockport’s poor mental health – yet the play barely does either, where a stronger critique could be usefully levelled at Anna’s confirmation bias. Fundamentally, she and Henry (though at odds) are deeply similar in their belief in technological solutions to national and global problems – even if she argues that people should give things up and have usage of various products restricted, in the case of antibiotics. Henry, on the other hand, is summed up by Smith’s neat epitomising quote: ‘You don’t tell an American to turn off their light; you build them a better light bulb.’

Underneath O’Reilly’s clipped, understated ruthlessness is a strange, somewhat undefinable personal history. When seemingly revealed, her backstory doesn’t really convince. A 12-year-old she briefly treated was wrongly given penicillin, despite an allergy. Officially, he died due to a ‘constellation of errors’ – a bureaucratic phrase which essentially meant that everyone got to wash their hands of responsibility. Yet though it confers a general sense of tragedy, there is structural disconnect in the play between her desperate attempt to improve mental health outcomes and the past she is trying to atone for. It would make much more sense, dramatically, for it to have been mental health or suicide related – though these are perhaps less likely to have been clinical errors.

Later on, we do find out (in passing), that her father was sectioned – lending more specificity. He thought he was a god, just like Henry, she says. As Smith wryly suggests, delusion works very differently, depending on wealth. Indeed, Henry’s delusional outlook, exemplified by his hypothetical cars, seems to be the thing that actually makes him money (while his company simultaneously haemorrhages money). Yet the control of information is rather muddled, and it does not seem clearly what we are supposed to make of Anna’s motivation. At the end, Anna says the reason she stopped treating patients was ultimately because she felt nothing when the child died. Yet her new mission does not logically follow from this either – unless we are to think that her plan to alleviate her own anhedonia is to treat the mental health of others?

The other main character, Nayra, shares the ruthlessness of Henry and Anna, yet she functions in the play too much as an obstacle and tool for the western characters – rather than a particularly nuanced figure in her own right. She secures the presidency, partly by manipulating Henry into buying controlling shares in the major advertising companies of the local television companies. Yet though she cuts Henry out of their deal once elected, Henry ends up getting his own back – mustering his vast personal fortune against, which he uses to literally rewrite history.

The play frequently works better in the minutiae of individual scenes than it does altogether – particularly true in Smith’s frequently inventive dialogue. Data miners are described as ‘binary truffle pigs’, while Henry’s poor grasp of Spanish has him identify himself as a ‘soy bean Americano’. The second half contains a call-back about quinoa that transcends all of the (many) jokes about hipsters I’ve ever heard during plays. Arguably the play would run more smoothly if it simply committed to being the gag-laden farce it sometimes is.

Yet for every compliment, one feels the gravity of play’s fundamental error. Rare Earth Mettle seems so attuned to the nuances of language, but this makes the excuse of ‘unconscious bias’ (as the Royal Court described it as in a 6th November statement on Twitter) all the more surprising. How could something so defined and specific in places have blundered so significantly?

Sometimes the play’s grasp of contemporary politics is razor sharp. As Anna and Henry vie for the rights to the salt flat’s lithium, they cite rather than obfuscate the toxic legacy of silver mining as part of their arguments. Perversely, the offer to repair (financially and literally) the damage of colonialism can now be leveraged in a business deal. Elsewhere, Smith considers compassion engineering – which builds difficulty into accessing products (for instance, the slow-release open of an iPhone box) to improve our haptic relationship to products (and, by implication, improve our loyalty). Here, Smith brilliantly examines how capitalism is not just a cold, free-market machine, but something which can turn its empathy on and off, depending on profit potential.

Similarly astute are observations about western service economies. ‘Ideas are the new coal’, Anna tells Kimsa’s daughter, Alejandra, while treating her cancer. She asks, in reply, what if they find ideas cheaper somewhere else? Moments like this skewer western supremacist ideas about the value of ideas themselves – yet they feel poorly integrated into the play as a whole. A brilliant scene sees Henry simultaneously blackmailing and bribing a Californian Professor of South American history into inventing an extra indigenous nation – exactly where the salt flats are situated. Money bends the truth with shocking speed. The start of the second half also has a memorable routine about keynote speeches and how companies need to sell a narrative. A high-end speechwriter, who has written for Trump, tells Henry that the best thing that happened to Apple was Steve Jobs was getting cancer.

Yet this is all they are: routines. Some are overplayed considerably, such as a running joke about mistranslation, which is hilarious in the opening scene but wearying by its third prolonged iteration. Kimsa’s desire to gather all of the main characters together in one place retrospectively seems like his chance to best them all – beating them all at their own game. Yet it also feels like the play wants all the characters back together for its denouement, which feels a little artificial.

Having used Henry’s influence to get himself declared a nation of one, and the sole owner of the salt flats, Kimsa’s natural resources seem to give him control. He agrees to sell to Henry, once he has the permission of his daughter. But she can only consent, Kimsa says, when she is 18, in six years’ time.

Late in the play, Smith suddenly finds a moral and emotional intensity lacking elsewhere in a terrific scene in which Henry and Anna argue, before agreeing to a horrifically manipulative deal for their mutual benefit. Smith scripts an electrifying discussion over the value of public healthcare – giving the devil’s advocate all the best tunes, but little that seems to stand up to scrutiny. It is hard to argue that the failure of NHS healthcare is poor value for money, when America spends around 17% of GDP on healthcare compared to the UK’s 10% – especially when, as Anna argues, ‘half the country’ can’t afford to pay. Yet in their scheming, they find common ground – the powerful climax finally fulfilling the potential of the play’s premise. Anna agrees to walk away, no longer treating Kimsa’s daughter, who will now likely die within a year, meaning Kimsa will agree to sell Henry the lithium. Money wins. I found it a profoundly moving note to end on, Carlos Gutiérrez Quiroga’s musical score almost imperceptibly heightening the emotional weight of the bleak ending.

As I have thought over Rare Earth Mettle this week, I have frequently thought back to the script of Harrogate – Al Smith’s beautifully wrought two-hander play which the Royal Court staged in 2015. Every moment of Harrogate is precision engineered to convey moral complexity, to wrong-foot and place the audience in an uncomfortable position as they watch the events on stage. It is probably one of the best British plays of the century so far and has a devastating sadness in it, especially towards the end. I longed for some of the same moral ambiguity and searching, tender writing here. There is a glimpse in the agonising final confrontation of Anna and Henry, when Anna says she’ll walk away if Henry says the name of the girl he wants to condemn to death. ‘Alejandra’, he says, after barely a pause. Yet the audience has largely been made uncomfortable not by complicity or complexity with its troubling characters, but by the theoretically excised antisemitism that still lingers heavily in the memory. There is a far better play in the midst of this material, but no one has been quite able to find it. With more careful dramaturgy, and greater cultural sensitivity, perhaps it could have been found.

Rare Earth Mettle

Written by Al Smith, Directed by Hamish Pirie, Design by Moi Tran, Lighting by Lee Curran, Composition by Carlos Gutiérrez Quiroga, Sound Design by Ella Wahlström, Movement Direction by Yami Löfvenberg, Starring Carlo Albán, Arthur Darvill, Jaye Griffiths, Genevieve O’Reilly, Marcello Cruz, Lesley Lemon, Racheal Ofori, Ian Porter, Ashleigh Castro, Giselle Martinez

Reviewed 22nd November 2021