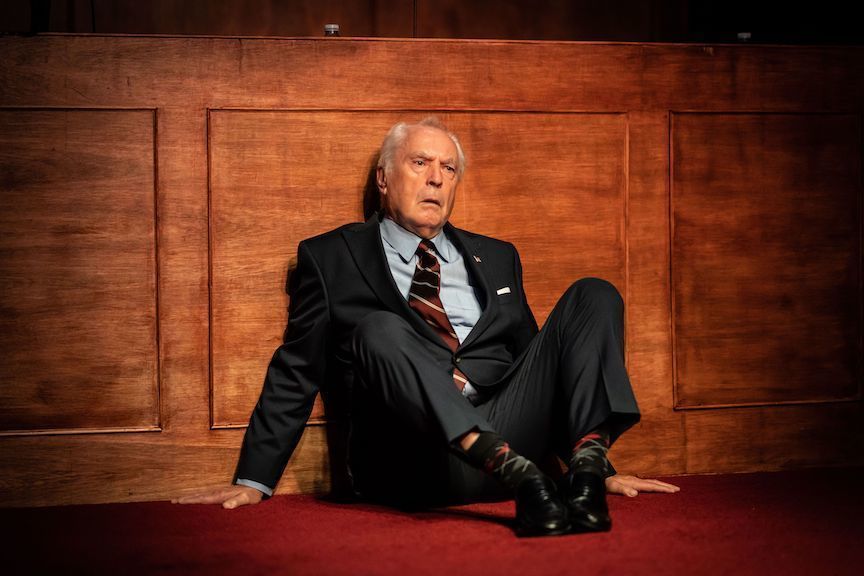

Joshua James in Yellowfin

This piece first appeared on the Crtimas newsletter, available here.

The fish have disappeared. This inexplicable, almost mythical happening underpins Marek Horn’s delightfully detailed new drama, Yellowfin, for the Southwark Playhouse. The strange premise vaguely recalls that of The Leftovers – in which two percent of the world’s population disappears instantaneously. Yet where the television series explored the implications of such an event for faith, Horn instead mines the political and legal consequences – as a group of American senators attempt to govern the ungovernable.

As much as it could have been an event of spiritual significance – or at least an impossibly rapid collapse of biodiversity – Horn suggests that such a disappearance would be most felt as a supply chain issue. Demand immediately outstrips the non-existent supply, so the price of tinned fish rockets. Governments make the sale of fish illegal, initiating an underground black market. Meanwhile, inventors start developing ‘squib fish’, but these artificial, laboratory-grown alternatives are texturally wrong – lacking in real fish’s distinctive ‘flakeage’. For a play set entirely within one room, the world of Yellowfin is remarkably detailed.

The play centres on a U.S. Senate Committee, a few decades after the fish vanished, chaired by three senators who question Mr Calantini – a former illegal fish salesman, brilliantly portrayed with a spiky defensiveness by Joshua James. Yellowfin starts by resembling the tussle of a legal cross-examination, with the witness Calantini really a suspect. Yet as the play progresses, the scope of the committee resembles something more like an enquiry. Unanswered questions left by the fish’s sudden disappearance are absent presences throughout the play, gaping like open wounds.

These questions, Horn suggests, are not suited to the processes of the courtroom though. Their rigorous respect for procedure often obscures more than it reveals. The script is peppered with almost reverent murmurings of ‘for the sake of the record’, ‘due process must be observed’ and the recurring mantra ‘let the record show’, spoken close to the microphone with an almost sacred reverence. Yet these phrases divert their discussion onto an almost prewritten script, away from difficult truths. Writing in Exeunt magazine, Brendan Macdonald noted how the senators’ legalese functions in part as a defence mechanism against fear. He writes that ‘red-tape procedure can be used as a sort of epistemological safety blanket for those terrified of the unknown’. Their uncertainty is based only in terrified speculation: if the fish can just go, then we could too.

They suppress their sheer terror at the potential threat to their own extinction by falling back on bureaucracy, mirroring contemporary measures against the climate crisis. The COP26 conference in Glasgow this year often seemed more like an exercise in logistics than a site of political resolution. Even the terms agreed upon ended up couching potential action in abstractly minimising degrees of warming, rather than considering the harm done by specific human behaviour. In Yellowfin, their fear is not only of the unknown (and their potential doom), but because of a painful possibility they cannot bear to consider. Maybe they caused the fish to go. Underscoring all of their actions is this unacknowledged guilt they try not to identify with.

Watching Yellowfin, I was reminded of a recent blogpost by Dan Rebellato, about Nicolas Kent and Richard Norton-Taylor’s play Value Engineering – which condensed the enquiry into the fire at Grenfell Tower on 14th June 2017 into a verbatim play. Like Yellowfin, Value Engineering is set within the bland, bureaucratic space of a tribunal, which Rebellato argues ‘evinces a naive realism’ – attempting to present facts ‘unadorned’ and reveal ‘the simple, damning truth’ of what occurred. As much as this aesthetic spareness might be driven by respect for the tragedy and injustice of the fire, the setting ends up being rendered in meticulously banal details, while the real events remain potentially remote. As Rebellato writes, ‘real lives and real deaths [are] only allowed to emerge as subtext’.

A small moment particularly stands out for me. Roy – the oldest senator, flickering between lucid profundity and forgetful nostalgia and played with sparkling energy by Nicholas Day – recalls that his family ‘lived in England at the time’. Calantini replies ‘I’m sorry to hear that’. We laugh along at what seems to be a well-worn punchline. How awful, to live in Britain. We assume it’s part of Joshua James’ precisely perfected sardonic shtick. But then he asks, in earnest, ‘Were they all drowned’. The laughter chokes as we piece together the throwaway clues Horn has seeded. England is now entirely underwater; ‘They were all drowned’. As fictional as it is, many audience members have just laughed at a tragedy – our own tragedy, in fact.

The ultimate purpose of the Senate Committee’s enquiry is to hear Calantini’s expert opinion on whether a can of tuna actually contains the high-quality Bluefin steak they desperately seek. We find out that Marianne, in particular, believes that the DNA of the Bluefin contains ‘secret information’ – which can be searched for and discovered. It could explain why the fish disappeared and potentially prevent it from happening again – this time to them. It’s a fanciful idea, but we can never be sure she is entirely wrong. Near the end of the play though, Calantini argues that false hope is making them enquire after information that cannot be found. Instead, just like their procedural language, this quest is shielding them from guilt and facing up to their potential responsibility in the fish’s disappearance. It ‘stopped us from having to look inside ourselves for an answer.’ In the play’s extended climate crisis metaphor, the answer is not necessarily difficult to discover, but tough to accept.

The play does conclude with a moment of delightful uncertainty though. With one last can of bluefin tuna remaining, pierced by a harpoon and going off by the second, Calantini encourages Roy just to eat it. ‘You’re a human being, Roy’, he says, ‘Act like one’. As the other senators panic, Roy blissfully consumes the fish inside, delighting in its flakeage. It plays on stage as a moment of transcendence – within an ironic, satirical framework, yet also sincere. Is this a metaphor for wasteful consumption and hedonic nihilism in the face of species-threatening events, or a more honest, human response to the situation? Perhaps it is preferable at least to the dubious social good which Marianne believes she is doing, hunting secret information and denying responsibility. Not all theatre is a moral quest, but pretending it is can take us further away from the answers we claim to seek.

After the play finishes, an usher hastily places a yellow caution sign over the mess left on stage, so that audience members don’t step in the remnants. There are no neat conclusions: just fish spilled across the floor. Something quite unlike a tribunal or bloodless courtroom drama has taken place, ending in an event which is morally and literally messy, but precise, detailed and perfectly textured.

Yellowfin

Written by Marek Horn, Directed by Ed Madden, Set and Costume Design by Anisha Fields, Lighting Design by Rajiv Pattani, Sound Design by Max Pappenheim, Starring Nancy Crane, Nicholas Day, Joshua James and Beruce Khan

Reviewed 6th November 2021