Katherine Parkinson in Much Ado About Nothing

Much Ado About Nothing, Shakespeare’s early entry into the now-perennial genre of the rom-com, is a knockabout comedy driven in both drama and humour almost entirely by rich character motivation rather than coincidence or contrivance. It contains perhaps Shakespeare’s greatest pair of lovers as leads and has more sophisticated wit than most of the other happy comedies. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Shakespeare celebrated marriage in the joining of couples who seemed desperate to marry but were prevented by strict laws. Much Ado internalises these restrictions, making it unusually psychological for a comedy, as Beatrice and Benedick insist on their lack of interest in – and even opposition to – the institution of marriage, only to be undone by love. Yet beneath Shakespeare’s idealising of marriage as an expression of romantic love, there simmers a darkness that can be hard to overlook in the way men treat women.

It makes perfect sense to stage Much Ado as a light-hearted show as a tentpole of a summer season, and the National Theatre have done so in their Lyttleton auditorium this year with Simon Godwin’s delightful production. The Sicilian setting of Messina is now the Hotel Messina, a glamorous resort for the rich and famous (this Beatrice is a starry actor), which invests the production with a sense of holiday detachment. The shadow of the war from which Benedick, Don Pedro and Claudio have returned is rather faint here, bar the umber combat fatigues they wear in the first act and Benedick’s soon-trimmed stubble. By contrast, Christopher Luscombe’s pair of 2014 RSC productions, Love’s Labour’s Lost and Much Ado About Nothing (there titled Love’s Labour’s Won), were set in a melancholy Edwardian England, either side of the First World War. Here, the 1930s is treated as an aesthetic, rather than a time of particular political significance. The conflict is an unspecific one used as little more than set dressing. Instead, Godwin focuses on the ‘merry war’ of words in the waspish relations of Beatrice and Benedick. All of the drama is simply interpersonal.

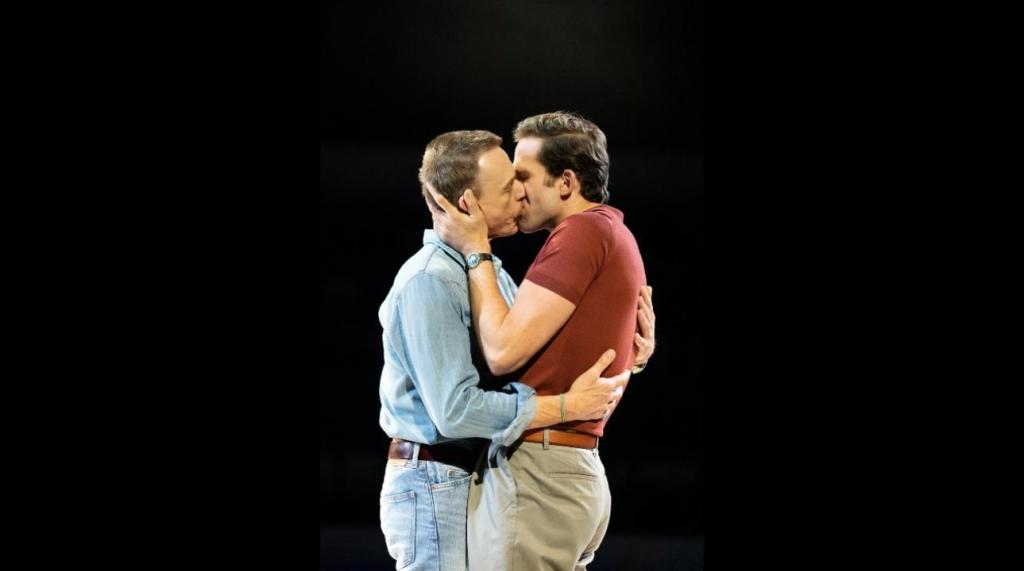

But what interpersonal drama it is. John Heffernan and Katherine Parkinson are brilliantly cast as the play’s famous lovers in denial. Neither of whom can summon the courage to make the first move, shielding their interest in the armour of mutual dislike. They tie themselves in Gordian knots, philosophically opposing marriage in the strongest terms. Benedick in particular disavows the notion of marriage as anathema to his fiercely independent spirit; to marry would be to submit to state of perpetual boredom that means you ‘sigh away Sundays’ in lieu of meaningful entertainment. Yet his obsession with not marrying is apophatic, pointing to the deep desires he is not yet ready to admit. He would only ever countenance marriage if a woman managed to have ‘all graces’ – ‘fair’, ‘wise’, ‘virtuous’, ‘noble’, ‘of good discourse’. (Here, Heffernan’s reading of ‘and her hair shall be of what colour it please God’ alters the original meaning that it may not be dyed to make Benedick seem more endearing; as long as she has all such qualities, he says, her hair colour is irrelevant.) Benedick constructs an elaborately reasoned logical house of cards for why no woman would ever be fit to marry him, yet it comes tumbling down with the play’s most touching romantic cadence, as Benedick realises that there is one woman who fulfils, even transcends, his criteria after all.

Getting Beatrice and Benedick, ostensibly the play’s main characters, to confess their latent feelings is debatably the A-plot, though it is Hero’s story which has the most plot significance and drama. Benedick and Don Pedro’s young soldier friend Claudio wants to marry the hotel-managing Leonato’s daughter Hero, though he is too shy. Therefore, Don Pedro sets out to woo her on Claudio’s behalf. Yet a rift between Don Pedro (Ashley Zhangazha) and his brother Don John (David Judge) threatens to break everything apart. Don John initially lies to Claudio, that Don Pedro is secretly wooing her for himself, yet this is lie is resolved with relative ease – though the trustworthiness of Don John remains undisputed. Thus, Don John confects a new rumour: that Hero is having an affair. Don John is a forerunner of Iago, albeit without the charm. He does not recruit our sympathies like Shakespeare’s tragic villain, and nor is he successful in steering the course of the play towards his intended tragedy – though for a time it seems like tragedy has occurred, for some of the characters. Yet Don John unleashes the play’s other great psychodrama (alongside Beatrice and Benedick’s mental prisons that restrain their love) – a fear of infidelity. To be married is to risk being cheated on. The horn imagery of cuckoldry is frequent in dialogue, even in Benedick’s celebratory lines at the very end: ‘there is no staff more reverend than one tipped with horn’.

The play is proof that tragedy and comedy is all about perspective, the final acts playing like a perspective trick in which most characters believe Hero has died from the shock of false accusation (a similar fate as befalls Hermione in The Winter’s Tale, and from which she also appears resurrected). Meanwhile, the audience share the knowledge of Beatrice, Benedick and Leonato – that Hero’s death is faked, while Don John’s lies are investigated. The restoration of Hermione in The Winter’s Tale could be viewed as a second go at the Hero resolution, with more artful stagecraft. Here, there is the business of marrying a suddenly remembered sister, a messier series of events that leaves Hero as a largely speechless bride.

For the most part, the production’s tone is utterly blissful, the verse delivered lightly (especially well by John Heffernan, who seems in his element here). It takes a lot of skill, on the part of actors and crew, to make Shakespeare look this easy. The more challenging or outdated pockets of Shakespeare’s language are never allowed to get in the way of the entertainment, any unfamiliar phrasing smoothed over by the brisk pace. As a result, a relatively low percentage of the laughs come from the original wordplay, yet this Much Ado has a somewhat more sophisticated take on Shakespearean comedy than simply padding out the play with anachronistic ad libs. Instead, almost every scene is invested with a potent sense of situation. Anna Fleischle’s wonderfully revolving set evokes the bustle of a busy hotel during peak holiday season, while also helping to place every scene in a specific location, inside or out, rendering the comic flights of fancy far more particular than just zany interludes to spice up the script.

At times, scenes are composed of two elements, relatively simplistically juxtaposed: Shakespeare’s original words and unrelated physical comedy. This is particularly notable in the scene where Dogberry, now the hotel’s security guard rather than the Constable of Messina, delivers pompous instructions to his juniors before sitting (as we know he inevitably will) onto a piled-high plate of spaghetti bolognese that has been inexplicably present on stage since the beginning of the scene. The scene progresses hilariously as his assistants try to clean the residue of Chekhov’s pasta off his trousers while he remains continues to speak obliviously. The original script here is conspicuously, deliberately secondary in importance. In the Dogberry scenes in particular, entertainment is the highest priority.

Other moments utilise random comic business to heighten not only the humour but the characterisation of the play, such as the mirrored scenes in which Beatrice and Benedick overhear that the other has confessed love for them in secret (in rumours set about by the matchmaking Don Pedro). Benedick’s is a particularly funny sequence; he cocoons himself in a hammock to eavesdrop but falls painfully onto the ground below on hearing of Beatrice’s alleged affections. He then clambers across the set to listen, before secreting himself in an ice cream cart to overhear more closely. In a sequence of pure farce, Don Pedro, Claudio and Balthasar help themselves to ice cream – in the full knowledge that Benedick is hidden inside the compartment now revealed to be the cart’s built-in rubbish bin. They gleefully spoon ice cream and shower sprinkles onto Benedick, while remarking on how strong Beatrice’s love is. At the end, Benedick emerges through the bin’s hole, streaked with residue and trying to remain composed – an extremely effective comic sequence, even if Shakespeare’s hand is nowhere near it.

Godwin directs something similar for Beatrice in the following scene. However, the ice cream routine is understandably hard to top, and he is hamstrung a little bit the order of the play. Comic logic would dictate then that the funnier Benedick scene goes second. The enjoyable clowning of the Beatrice scene is entertaining (she ends up entangled in a beach changing tent, adopting the uniform of a passing porter), but it is not quite as viscerally amusing, lending it a slightly repetitious sense of anti-climax. It is unfortunate, but largely the case, that in this production the men are allowed to get the biggest laughs – both from their wit and their humiliation.

The thinness of the female roles is felt noticeably in Ioanna Kimbook’s performance of Hero, which exposes the writing’s limitations, as many strong actors’ interpretations of Shakespeare’s female parts do. Kimbook wrings as much emotion and nuance as she can from a part that asks only that Hero is charmed into silence and then victimised. Particularly good are the scenes where Hero is enlisted into misleading Beatrice. Hero coolly intones about Benedick’s apparent affection for Beatrice, while getting hugely and hilariously frustrated at her companion’s unconvincing woodenness.

This production struggles to sell the romance with Claudio though. Eben Figueiredo plays him as fairly meek at first, which is pretty much as Claudio is written, youthful and shy, but this makes Hero seem even meeker in her silent delight at the match. The intention seems to be for a sweetly dorky union of two shy people, Beatrice’s meta-joke ‘Speak, count, ’tis your cue’ followed here by a comically protracted silence. Neither can find the words, at least in public, and the silence can only be broken by a kiss. Yet the result makes both characters seem a little too dramatically inert, Hero so unknown to us at this point that her silence is hard to read as either being overwhelmed with love or full of uncertainty and reservation. The first act is the production’s weakest (and possibly the play’s too). The substitution of Don Pedro’s villainy (in the mistaken belief that he is wooing Hero for himself) for the real cruel intentions of his brother Don John later on could be a highly dramatic tale of the psychology of betrayal – central to the play’s themes of misbelieved rumours, for good and ill, and adultery. Yet it plays out here as an unfortunate longueur in this otherwise snappy take, delivered with not quite enough dramatic intensity.

The other point at which the production comes a little unstuck is at the dramatic peak – the apparent revelation that Hero let in a gentleman at her window during the night before her wedding, revealed only during the ceremony itself. Claudio has been cruelly tricked by Don John and his associates (he mistook Margaret and her lover for Hero), but that cannot excuse the ferocity of his response – nor that of every male character in the play, bar Benedick and the good-natured friar, who discovers he will not be marrying anyone that day after all. It is, of course, in the original play, but the lightness of Godwin’s interpretation elsewhere cannot be easily squared with the torrent of pure misogyny unleashed into the play, which would feel unnecessarily cruel even were the accusations true.

The convivial Leonato has until then proved to be a warm and gentle father, blunting any of suggestions that the match of Claudio and Hero was arranged against her will. Yet now he turns into a toxic combination of Egeus (Hermia’s cruel father from A Midsummer Night’s Dream) and Leontes (the jealous king who flies into a rage, wrongly suspecting his wife Hermione of adultery in The Winter’s Tale). Leonato wishes his daughter dead, Rufus Wright playing the anger in a serious, violent register: ‘Death is the fairest cover for her shame that may be wished for.’ Patriarchal anger is certainly a valid tone to strike when staging Shakespearean comedy – which is often filled with dark, violent and threatening moments. However, it seems fundamentally jarring with the earlier tone of playfulness and even more so with the relative ease with which the play’s tensions are resolved. It is hard to feel that all can be simply and immediately forgiven – with either father or fiancé – especially as Hero has so little agency in the play’s ending, treated like a prop who can be summoned at will to complete the marriage as if nothing has changed.

The text itself gives only scant acknowledgement to the mountain that must be climbed to resolve the animosity of Claudio in particular. Claudio strikes a tone of attempted amity, but he misdirects the apologies towards a father who has just condemned Hero as strongly (believing Hero to be dead). Figueiredo impressively delivers the speech where Claudio asks him for forgiveness, diverging from Shakespeare, who has Claudio plead his innocence – saying ‘sinned I not, But in mistaking’. Figueiredo’s phrasing instead emphasises contrition over his technical (and extremely dubious) innocence. Godwin tries to enrich Hero’s meagre portion of lines by amending the script with lines from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 29, which she intones from under a veil at the funeral procession being held for her. The line ‘Like to the lark at break of day arising from sullen earth’ takes on the spinetingling register of resurrection, as she will seemingly rise from the grave in the next scene. Yet its deployment is largely to paper over the text’s utter silence on whether or not she still loves Claudio. Godwin’s answer is that she does, even if we can barely see why.

It is also curious that Shakespeare presents such an unusually brisk resolution. The final scene runs to only 120 lines and contains the unions of Hero and Claudio, Beatrice and Benedick, and the entreaty that Don Pedro ‘get thee a wife’. The equivalent scene in Twelfth Night runs to 400 lines, Measure for Measure almost 550, while Love’s Labour’s Lost closes with the longest single scene in Shakespeare – a notorious 900 lines (over a third of the entire play). While Much Ado has somewhat less ado to remedy in the final scene (in terms of pure plot mechanics at least) than any of these plays, there is perhaps a greater deal of emotional complexity to deal with. Shakespeare seems to sidestep the difficulty of emotionally rehabilitating Claudio and Hero’s marriage; instead, he makes it work only practically, in securing Leonato’s consent. Hero’s willingness to marry and her forgiveness will always be an issue for a director of the play to negotiate, and Godwin’s decision to play it relatively straight (bar the added sonnet) does not fully assuage our potential concerns.

The show closes with a joyous musical number, performed by the entire cast and the jazz band who pop up charmingly throughout. No notes of melancholy remain; all is forgotten by the characters on stage, but whether we can forget is quite another matter. The tone is so fantastically calibrated for the most part – Heffernan’s attention-seeking impishness mixing particularly well with Parkinson’s blend of ice and acid. Yet the limits are exposes in the Hero plot. The recurring issue of whether Shakespearean men deserve forgiveness is hardly improved by going so unacknowledged. Despite this, Godwin’s production channels its actors’ brilliant chemistry into one of the most entertaining and watchable Shakespearean comedies I have ever seen, even if this comes at the cost of the overlooking play’s more challenging darker depths.

Much Ado About Nothing

Written by William Shakespeare, Directed by Simon Godwin, Set Design by Anna Fleischle, Costume Design by Evie Gurney, Lighting Design by Lucy Carter, Movement Direction by Coral Messam, Composition by Michael Bruce, Sound Design by Christopher Shutt, Fight Direction by Kate Waters, Associate Set Designer Cat Fuller, Music Associate Lindsey Miller, Company Voice Work by Jeannette Nelson, Staff Director Hannah Joss, Dramaturg Emily Burns, Music Direction and Guitars played by Dario Rossetti-Bonell, Drum Kit played by Shane Forbes, Upright Bass played by Nicki Davenport, Woodwind played by Jessamy Holder, Trumpet played by Steve Pretty, Starring Katherine Parkinson, John Heffernan, Ioanna Kimbook, Eben Figueiredo, Rufus Wright, Ashley Zhangazha, David Judge, Phoebe Horn, Wendy Kweh, David Fynn, Al Coppola, Celeste Dodwell, Olivia Forrest, Ashley Gillard, Brandon Grace, Nick Harris, Kiren Kebaili-Dwyer, Marcia Lecky, Ewan Miller, Mateo Oxley

Production Photographs by Manuel Harlan

Reviewed 23rd August 2022