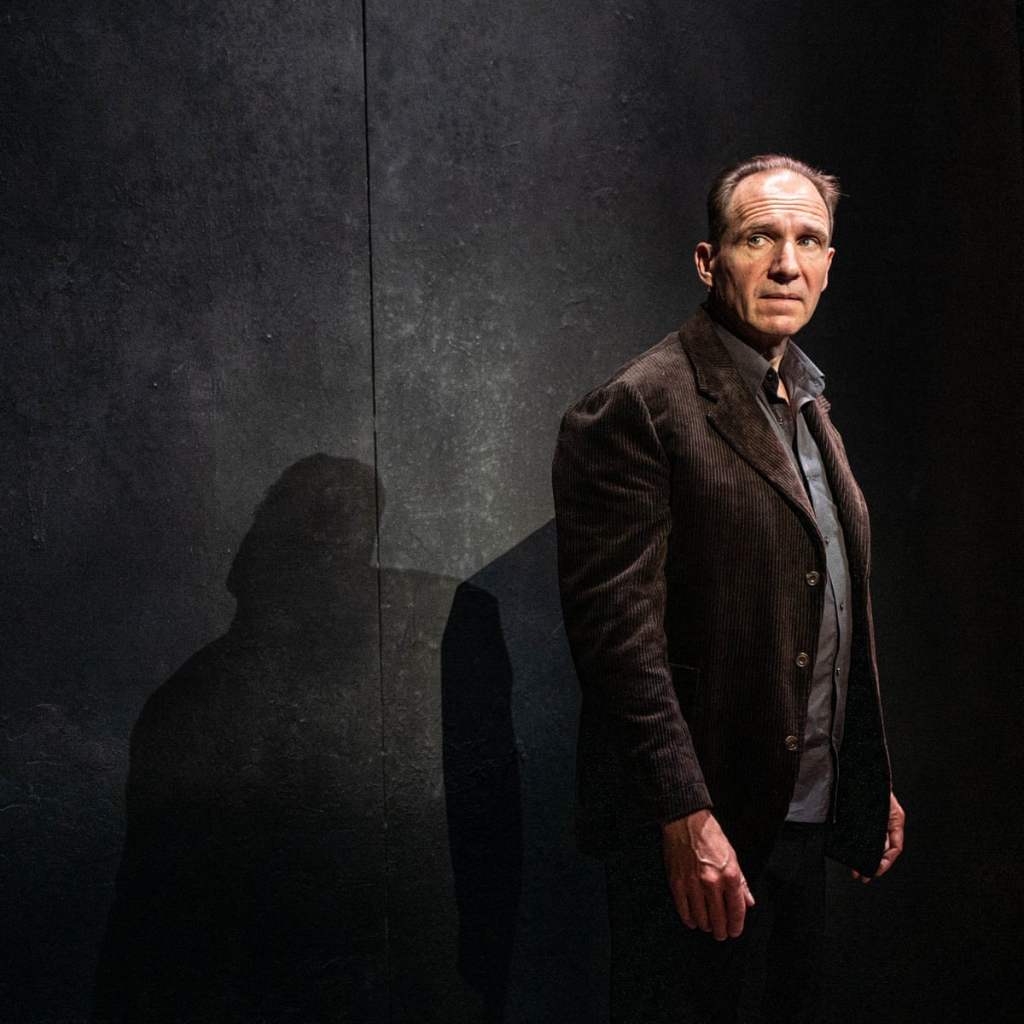

Ruth Wilson in The Human Voice

Ivo van Hove’s production of Hedda Gabler played on National’s Lyttelton stage to considerable acclaim in 2016, so the news of another collaboration between the garlanded director and lead Ruth Wilson sets high expectations. Unfortunately, this production of Jean Cocteau’s often-adapted 1930 monodrama struggles to fulfil them.

Like their Hedda, also designed by Jan Versweyveld, The Human Voice plays in a near-empty void of white space. Hedda Gabler’s set had the sparsest furnishings of a modern home, punctuated only with a few objects of either essential function or immense significance (a gun, flowers, an upright piano). The Human Voice pares things back even further. Wilson is placed into a vacant white box, which she sometimes brings props into, yet unlike before the effect is not of a gaping emptiness, but a claustrophobic, restrictive container. We see Wilson only through a window, so she is letterboxed in widescreen, hemmed in, her suppressed emotions soon filling the space. She seems trapped behind the glass – like it is a petri dish, a display case, or even as if she is under the slide of a microscope. Yet despite Wilson’s best efforts, this suffuses an air of cold, scientific sterility into the play’s atmosphere.

Peering through the glass, there is an inescapable and palpable sense of voyeurism, and surely van Hove knows this. However, he does little to challenge us or problematise our presence. The show casts us as curtain-twitching onlookers across the street – or from another nearby tower block. (We realise that here she is high up once she jumps to her death.) Yet we hear her only down the telephone, almost as if we are her lover – hearing her often ASMR-like amorous overtures down the phone, flickering in an instant between dismissive and desperate. Thus, we are both sought out and blamed.

Perhaps the ethical complications van Hove seeks to entertain are stymied by the unfortunate fact that the show offers fairly few theatrical pleasures. Though fans of Wilson will relish the chance to see her on stage again, the production is languorous and lacks energy. Were we really gazing in through her window, I doubt we would carry on watching. Though running at only 70 minutes, the sheer aesthetic austerity of the play – a deliberate reflection of her mental state though it is – tests one’s endurance a little. The greatest variation comes from the terrific sound design, the lighting swelling from cool white to a pungent yellow, or the occasional opening of the window. Any attempt to goad us into guilt about what we are watching would rely on us being problematically riveted, rather than somewhat indifferent.

The main source of life in the play is music – some diegetic, some as additional soundtrack. At the start of the play, she listens to Arlo Parks’ ‘Hope’, with its recurring refrain ‘You’re not alone, like you think you are’. As a statement on how technology connects, it seems logical, while it also creepily suggests our presence as the voyeuristic audience. It also foreshadows, with tragic irony, the woman’s eventual lonely fate. Later, her melancholy is telegraphed by the onset of Radiohead’s ‘How to Disappear Completely’ – a gently meandering ode to dissociation, which is actually one of my favourite songs. Yet even so, here it felt like an underearned attempt to overlay emotions that we were not quite feeling – largely due to the alienation built into the design, rather than Wilson’s acting.

The track recurs through the play, its first use the most creative – though the third and final (near-complete) playthrough is the most artistically daring. Wilson plays music on her phone, dancing to Beyonce’s ‘Single Ladies’ – another song laden with an ironically literal relationship to the drama. Yet Radiohead fades in and eventually drowns it out. The music is implicitly internal – reflecting her true state of lifeless, out-of-bodily sadness. However, the effect seems too deliberately composed and imposed, a shortcut to emotion that does not fully satisfy. The third time ‘How to Disappear Completely’ plays, Wilson sits inertly against the back wall. She does not move a muscle for a full four minutes, in a daring gambit. Yet, by this point, even a track as liltingly beautiful as this one has started to feel cheapened and overused.

At the play’s conclusion, when Wilson’s character dons an electric blue evening gown and pulls open her apartment’s sliding window to jump to her death, van Hove and Versweyveld’s sudden plunge into darkness is almost immediately interrupted by a blast of Miley Cyrus’ song ‘Wrecking Ball’. The choice is downright bizarre and feels crassly misjudged, disconcertingly dissonant with the play’s previous aesthetic of beige severity. It feels like a glib reaction to a woman’s suicide, especially when she acts not out of an excess of passion and spurned rage (as in Cyrus’ lines ‘I never hit so hard in love’ and ‘All you ever did was wreck me’) but out of a slump into deep depression.

In the scenes leading to her suicide, van Hove transposes some of Cocteau’s phone-bound dialogue into a direct audience address – which reaps some of the most effective moments of the evening. ‘I am suffering’, she tells us, and it is as if she is pleading for empathy – rather than being the subject of scrutinised, distant sympathy. She even says she knows it is difficult to keep listening. Afterwards, I wondered if many of the effects of the production are deliberately designed not for in-person thrills. Perhaps instead this version of The Human Voice should creep up on you later on. A couple of weeks on from seeing it, I find there is some truth in this, but there is so little stage action to hold on to that the specifics of the production do slide from your memory. Arguably the small creative team of van Hove, Versweyveld and Wilson are trying to show the difficulty of catching someone before they fall into depression – that such experiences (both for the sufferer and the attempted provider of support) are tiring, exhausting and sometimes even dull. In this production, as much sympathy as Wilson makes us feel, you can understand why answering the phone to her character becomes difficult – despite her pleas to be heard.

It does not help that we are so remote from her that the action fails to recruit much more than general sympathy. She is pitied rather than mourned because we rarely get the chance to ache with her. Suffering is the spectacle here; she has been placed here for our amusement, but it is not quite compelling enough for us to feel guilty about watching. In light of this, her death almost seems like she is opting out of the drama itself – realising there is no way to transcend the stage-box she has been trapped in, but that perhaps that she could deprive her observers of the ability to study her pain.

Though The Human Voice seems perfectly positioned for a free adaptation that grapples with the human cost of lockdowns, this version feels too generic, and too disinterested in the theme of isolation itself. Though the play has been advertised with the tag line ‘We’ve never been more connected. We’ve never been more alone’, we are not invited to share the woman’s plight, just to watch it – in a way that would be problematic, if it was more compelling.

The Human Voice

Written by Jean Cocteau, Adapted and Directed by Ivo van Hove, Design by Jan Versweyveld, Starring Ruth Wilson

Production Photographs by Jan Versweyveld

Reviewed 25th March 2022