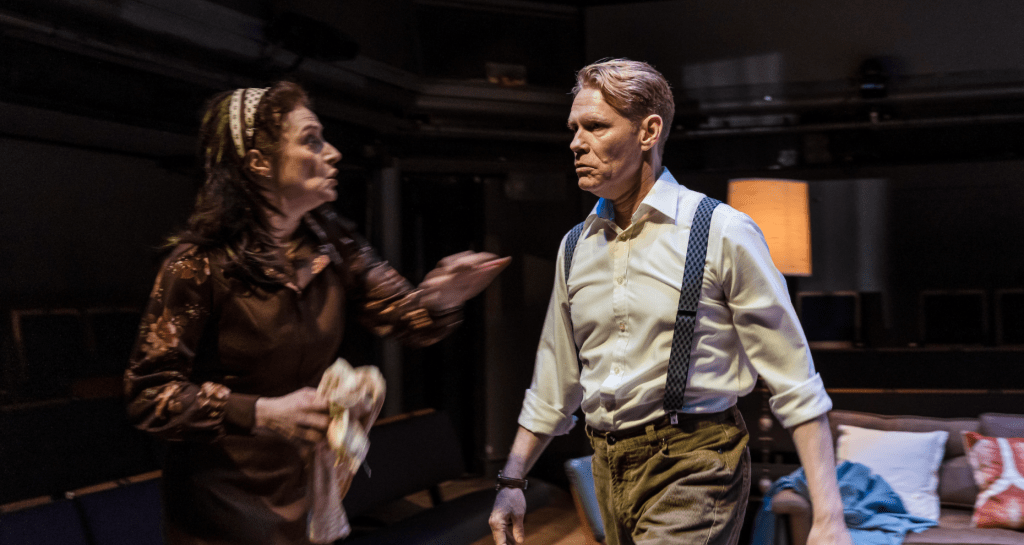

Eileen Walsh and David Walmsley in Girl on an Altar

At a talk she gave, I once heard Marina Carr discuss how she avoids writing chorus parts when adapting Greek tragedy – as they are often quite ‘boring’. It is certainly true that their dislocation from dramatic action is less immediate and engaging for some audiences more used to naturalist realism. Yet what struck me so much about Carr’s superb Girl on an Altar is the way that this free adaptation and extension of Aeschylus’s Agamemnon (the first part of The Oresteia trilogy) replaces the chorus with something other than straightforward dialogue. The painful recollection of Iphigenia’s sacrificial death a decade earlier, which is recalled at the beginning of The Oresteia, is no longer a vividly graphic summary (though it remains vivid and graphic) but an introspective deliberation from Clytemnestra, firing the starting gun for her eventual murder of her husband. The play follows in this pattern; each character becomes a filter through which subjective narratives pass, in long, poetic monologues, interspersed with occasional dialogues.

Annabelle Comyn’s direction – which coaxes passion and precision from a hugely impressive ensemble – relishes the effects of these delightfully unreliable narrators. Often the stage action contrasts the dialogue in subtly destabilising ways. Agamemnon’s infamous fatal bath is relocated to a bed on stage, but not in speech. It happens more subtly in narration of emotion; a character might remember a smile that the corresponding actor does not give, for instance. These moments sow subtle distrust as to whose version of events is accurate.

Carr’s dramatic gesture here is distension – opening up the time between Agamemnon’s return and his murder by days, even weeks. The timing is somewhat ambiguous, yet Aeschylus’s observation of the unity of time is purposefully discarded in favour of a passionate slow burn of love and hatred. As in many Greek tragedies, Aeschylus sets the action of Agamemnon just outside the family home, and the fateful cries of pain and anguish are typically heard from within – offstage. Carr instead takes us inside, the marital bed sitting prominently in the centre of the space. As Cilissa remarks, Clytemnestra and Agamemnon need time to ‘grieve and seethe’ in private – rather than the relatively more public scenes of the original Agamemnon. This (ultimately failed) attempt at healing and restitution is exactly what Girl on an Altar stages.

With its intergenerational struggle and murdered kings, The Oresteia certainly has affinities with Hamlet – with Clytemnestra as a far more active parallel to Gertrude, doing the deed herself and remarrying the cousin rather than the brother to maintain power. In this mould, Clytemnestras are often presented as either scheming and cruel, or madly emotional. What Carr does here is essentially to cast her as Hamlet himself – deliberating for two and a half hours over the right course of action as she battles with the complexities of love, anger and loathing she feels towards her husband and his actions. This grieving, seething mix is encapsulated in the blazing performance of Eileen Walsh, whose compelling stage presence communicates effortless authority and searching vulnerability at once. This is an all-time great Clytemnestra that refuses to mute her humanity in any way by dismissing her actions as mad, over-emotional, or self-interested and scheming. This Clytemnestra endures the agony of living with dignity and power, though letting go of her grief is impossible. Meanwhile, David Walmsley refines his take on Agamemnon as the play progresses, brilliantly conveying a mellowing from initial brutishness into a subtler, more sensitive figure choked up with pressure and regret, before he descends once more into irrepressible barbarity.

The title’s indefinite article hints at Girl on an Altar’sunderlying contention – that the horror of Iphigenia’s murder is not only the act of filicide, but the fact it presages a paradigm shift, after which sacrifices of daughters are normalised, even expected. The girl on an altar is in the process of becoming a savagely iconic image. Carr seems deeply concerned by the power of the image on the imagination. Clytemnestra learns that a similar sacrifice was made by Agamemnon in Troy, of Hecuba’s daughter Polyxena – in order that the winds would blow them back home. Drawing on both The Trojan Women and Hecuba by Euripides, Carr has Clytemnestra remark that ‘They sacrificed another girl before they left. […] One of Hecuba’s daughters. They say Hecuba was there.’ The events rhyme but are not identical; Clytemnestra’s spare dialogue rings with her still raw anguish and guilt that she arrived too late to see her daughter’s murder. (In this version, when Clytemnestra arrived there was already sacrificial ‘[b]lood on the stones’.)

The image of the sacrificial girl is potent and contagious, Clytemnestra desperate to stop the spread. She recalls that in the past ‘if a sacrifice was wanted it was a calf or a deer. Now it’s girls. The blood of spotless girls these new gods want.’ Carr situates the play in a world not entirely bereft of women’s rights – albeit within rigid class hierarchies – but where the limited rights women already have are under significant threat. An overtone of contemporariness wafts through the drama, but Carr feels no need to make the parallels explicit. Rather than reproductive rights or healthcare, it is the sacrifice of female children that is the new frontier here, and these killings are emblematic of a regressive renegotiation of the place of women in society. Even the king’s daughter is not safe. Clytemnestra dryly remarks that (for Agamemnon, and Greece as a whole) these sacrifices are ‘becoming a habit’, following the parallel sacrifice of Polyxena. What has been read previously as a concluding tragic echo of the sacrifice that began the war is convincingly situated instead as a continuation of an alarming, misogynistic trend. The play never entirely punctures the divine authority of the gods – though there is perhaps a subtle agnosticism towards the sacrifice’s causation of the winds. Yet Carr absolutely connects the pernicious effects of religious and superstition to violence against women. The gods themselves seem pliable to received wisdom and social prejudices. After all, Clytemnestra emphasises that they are ‘new’.

The danger of images is also apparent in the construction of heroic masculinity. When Agamemnon slays his daughter and dances on the altar, he retrospectively admits that it was as if Hercules was in his blood. We are left to judge whether this gauche celebration stemmed most from peer pressure, the expectations created by idealised heroes such as Hercules, or simple self-aggrandisement and ego – that he, like Hercules, might himself ascend to Mount Olympus and become god-like, if not a god himself. The violent mythical hero Hercules sets an alarming precedent. Hercules too killed family members – murdering his wife and sons in a fit of madness. (This usually is said to have presaged his twelve labours, as atonement, yet in Euripides he kills them on his return.) Carr’s drama is laced with a suspicion of such archetypes – not least the titular doomed girl on the altar, but also the masculine hero, and the mad wife. There is always greater complexity beneath the surface, whether one is a hero or a villain.

A final striking image echoes The Oresteia’s language quite directly. Where Ivo van Hove recently interrogated the social effects of war, violence and anger in Age of Rage, Carr seems far more concerned about the effects of war in private – and most of all, the way gender structures the world. This manifests, upon Agamemnon’s return from Troy, in his narrated decision to reassert control over Clytemnestra through patience, rather than simply dominating her. ‘All flowers bend towards the sun’, he says, foreshadowing his later claim of god-like status. He goes on: ‘She needs the yoke again but I won’t force it yet.’ Agamemnon thinks he is being reasonable, when in fact her is merely advocating a slightly less oppressive form of misogyny than physical violence.

Yet the image of the ‘yoke’ – a crosspiece which was fixed around the necks of two oxen in order to draw a plough – is hugely important in The Oresteia. Agamemnon and Menelaus are called ‘Atreus’ sturdy yoke of sons’, between them driving Greece to military victory. Aeschylus, in Robert Fagles’s translation, makes this image an extended metaphor; Agamemnon ‘slipped his neck in the strap of fate’, in his determination to sacrifice his daughter for military advantage. Yet the image is also replete with submission and control. When placed on the altar – desperate to avoid her screaming – Iphigenia is gagged, bridled. Fagles renders Agamemnon’s instruction as a conscious echo from the chorus: ‘slip this strap in her gentle curving lips’. Here, the horrifying outrage of her death is not only the substitution of a young girl in the place of a ‘yearling’, but the fact that, until moments earlier, it had been Agamemnon in the metaphorical straps. Now, Iphigenia is literally restrained. (This Aeschylean substitution is alive in Carr’s script too, notably in Agamemnon’s metaphorical defence that ‘My hands were tied’ by the army’s pressure on him, met by Clytemnestra’s literal retort, ‘Iphigenia’s hands were tied.’) Carr has Agamemnon claim that Clytemnestra should belong in the yoke – that ambiguous place of both child murdering warrior and female victim. His repressive misogyny is made all the harsher by the echo of Iphigenia’s stifled scream; female voices are crushed into silence.

The play’s structure is perhaps akin to a psychological thriller – a whydunit that simmers with not only hatred and vengeance, but the agony of love. Unlike the original Agamemnon’s dramaturgy of relatively straightforward retribution and descent, Carr’s drama thrums with life in the oscillations. Agamemnon’s decision is now the result of immense pressure, rather than simply the ‘frenzy’ of war-lust; he may have danced upon the altar, but his inner thoughts and feelings are ambiguous even to him. Furthermore, The Oresteia is usually grounded in clear patrilineal trauma (from Tantalus, to Pelops, to Atreus, to Agamemnon – and then to Orestes, in parts two and three, The Libation Bearers and The Eumenides). Yet for Carr, it is not only the house of Atreus which is haunted by spectres of violence and madness. Clytemnestra mentions that ‘My mother went mad’ – another intergenerational trauma, amid the traditionally male terrain of inheritance. She even names her child, with Aegisthus, Leda – the same name as her mother.

Clytemnestra’s love for Agamemnon is startlingly complex too. It is sexually passionate, yet warmly loving beneath that – evincing far more than a simple dichotomy of enemies and lovers. Yet they cannot be together without opening old wounds. In a long scene, actually set in their bedchamber, Clytemnestra confronts Agamemnon, eventually coaxing an admission from him: ‘Okay. I killed her.’ This is greeted with a sudden passionate kiss – culpability as aphrodisiac, yet in that admission their relationship might still have a future. Carr’s text, like Aeschylus’s, is largely free from stage directions; the lustful passion between them is brilliantly interpreted by Comyn as intensely physical. Yet it is the fact that Agamemnon cannot bear to remain in this position as an apologetic supplicant that speeds the play towards its bloody climax. Instead, he reasserts his authority and orders Clytemnestra and Leda are sent out to the harem of captive women, where Leda will soon die.

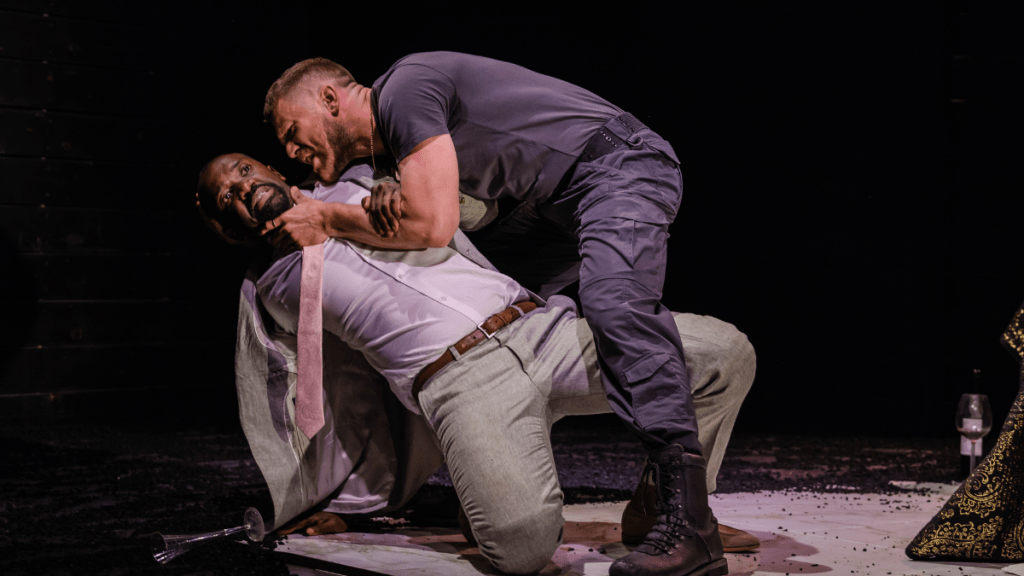

The play, rather surprisingly given the more domestic scope of Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, transforms in the second half into a full-blown war play – at least for the male characters. In one particularly exquisite moment of gendered scenography, the women sit around the bed in a tableau of silent, peaceful contemplation, while the men stand tall and bellow military commands. With the captured Clytemnestra offstage, Carr elicits many spinetingling moments from the excavation of the minor female characters. The nurse, Cilissa, originally only from The Libation Bearers, is now a significant figure, as a ‘servingwoman’ to Clytemnestra whose agency and power is frequently examined. In a startling moment, when Cassandra desperately complains that Agamemnon has kept her from her children, Cilissa replies ‘Your children? What about my children? Don’t talk to me about children.’ Kate Stanley Brennan, so often on stage here, unleashes the line as a sudden, flooring grenade, tearing through the drama of the royal household with a reminder of how their violence harms more than just themselves.

Also impressive is Nina Bowers’s astonishing Cassandra. Robert Icke, who staged The Oresteia in a 2015 production at the Almeida, has argued that while the traditional reading that Cassandra is a ‘sex slave’ who Clytemnestra is jealous of is understandable, the play could also be read more sympathetically that Agamemnon is ‘try[ing] to rehabilitate a version of Iphigenia’ – ‘someone who could have been put to the knife and wasn’t’. (She is Hecuba’s daughter – who, unlike Polyxena, survives the fall of Troy.) Icke ensured that the relationship between them was still fraught with a power imbalance and potential abuse yet interposed an additional ambiguity. Carr also complicates the character, refusing often-typical mumbled prophecies and anguished screams, and giving Cassandra the role of narrator; her prophecies are now authoritative. Bowers delivers the play’s haunting final line: ‘And then, as foretold, she comes for me.’ The lights plunge into sudden darkness, with that breath-taking rush of emotion the best plays manage in their closing moments. In this conclusion, the original trilogy’s tragic cycle of murders is leant a new shape. Cassandra is no longer ancillary to the revenge killing of Agamemnon. She is the substitute Iphigenia who Clytemnestra has now killed, and Clytemnestra, in part, becomes what she despises.

Girl on an Altar

Written by Marina Carr, Directed by Annabelle Comyn, Design by Tom Piper, Lighting Design by Amy Mae, Composition and Sound Design by Philip Stewart, Projection Design by Will Duke, Casting Direction by Julia Horan CDG, Movement and Intimacy Direction by Ingrid Mackinnon, Voice and Dialect Coaching by Daniele Lydon, Costume Supervision by Isobel Pellow, Assistant Direction by Jessica Mensah, Starring Nina Bowers, Daon Broni, Jim Findley, Kate Stanley Brennan, David Walmsley, Eileen Walsh

Production Photographs by Peter Searle

Reviewed 31st May 2022