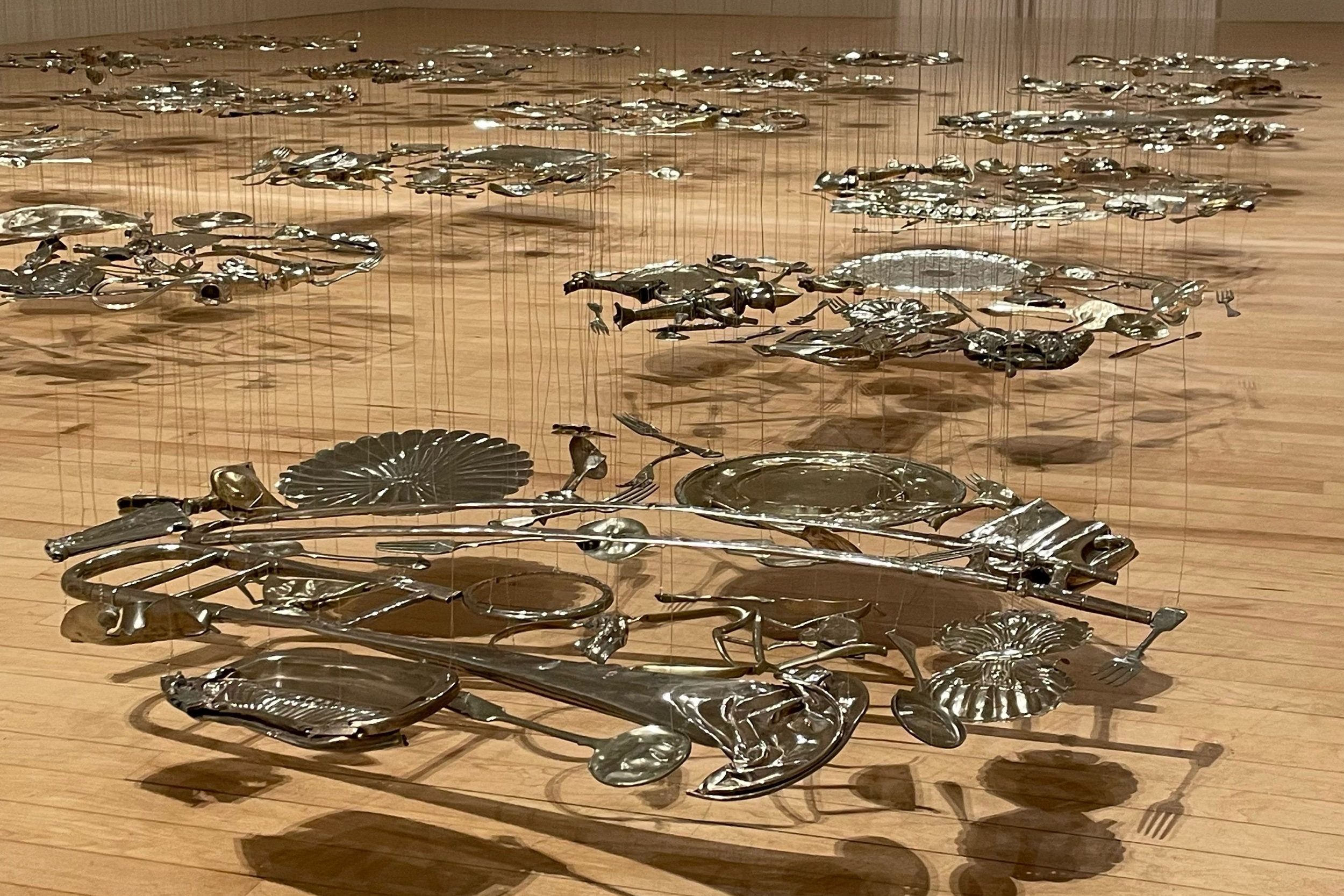

Tom Hollander in Patriots

A gifted scientist, led by infinite ambition and limitless imagination, creates a monster which grows beyond his control. Frankenstein, Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel of ambition, inquiry and overreach, has given us tropes that are now familiar. It provides a cautioning message to anyone who believes they can transcend human limitations – part-Prometheus, part-Icarus in its mythic warning. It also takes the fatal flaw which usually undoes a tragic protagonist and externalises it – an unwitting self-destruction.

This narrative shape is put to excellent use in Peter Morgan’s new historical drama, which dramatises the life of Boris Berezovsky (in this case, a gifted mathematician rather than experimental scientist) as the genius who is blind to the dangers of his own creation – until it is too late. Patriots largely operates as a biography of Berezovsky, from his early childhood (he was born in 1946) to death by suicide (in 2013). Yet by the second half, it becomes less the story of Berezovsky as the origin story of an even more significant figure: Vladimir Putin.

Tom Hollander, who seems subtly but significantly to improve everything he appears in, plays Berezovsky marvellously. He is frequently light and fun, leavening the play with delightful swings between razor-sharp focus and confidence, and bathetic notes of self-pity. His darkly vindictive side emerges on a hair trigger. Yet beneath this all, a pungent melancholy pervades his homesick Russian soul, when exiled from Russia by the very man he promoted. In flashback sequences, Hollander embodies the impishly arrogant child Boris, showing him gradually turning away from his childhood passion of mathematics and his determination to win a Nobel Prize: ‘They pay a million dollars’. (Asked what he would do with the money, he simply replies, ‘Gloat.’) Instead, Berezovsky becomes a titan of Russian commerce – one of the first big businessmen to operate there after the collapse of the Soviet Union, raring to go from the moment Gorbachev ‘permitted small-scale private enterprise.’ Berezovsky saw an opportunity and seized it, his luminous imagination envisioning the chain of events that would lead to Russia’s increasingly capitalistic economy and allowing him to prepare. He is obsessed by the infinite and limitless; ‘Ambition’, he says, as a child, ‘is the belief that the infinite is possible.’ Whether that works in practice, rather than just on paper, is another matter.

Berezovsky repeatedly cites his degree in decision making mathematics – especially as leverage in business deals. He can tell them, with scientific confidence, that they are making a good or bad choice. Yet Morgan seeks to expose how complex calculations can go awry when mapped onto real, unknowable people. Morgan and director Rupert Goold withhold just enough from us that a chance encounter in Act One Scene Six crackles into life with sudden realisation and humorous surprise. Attentive viewers will already realise that the Deputy Mayor who Boris is unable to bribe is Vladimir Putin, but it is easy to miss his identity – particularly as Will Keen plays him with a powerful anti-charisma, at first, softly spoken, austere and seemingly banal. Held back as a sudden shock is the revelation that the ‘kid’ – in Boris’ words – who he is reluctantly meeting is Roman Abramovic, known for his regular press coverage as the former owner of Chelsea FC. Morgan stages their meeting as a deliberate jolt; ‘Roman Abramovich. Vladimir Putin,’ says Berezovsky in a mutual introduction which hammers home just how timely this drama will be. The bit players are soon to become protagonists in their own stories. Meanwhile, Berezovsky is unaware of the potent dramatic irony as we see his inevitable downfall in the mere presence of the apparent inferiors who will outgrow him.

Abramovic is played as magnificently bashful by the brilliant Luke Thallon, who shone recently in Camp Siegfried and After Life, as well as the Almeida’s original 2017 production of Albion (also directed by Goold). Like Putin, Abramovic is another Russian of immense geopolitical significance who Berezovsky appears to create. He acts as a ‘Krysha’ to Abramovic, an almost familial relationship, a form of business protection, support and sponsorship. The word literally means ‘roof’. In return, Berezovsky receives informal, undocumented payments – which amount to at least fifty percent of Abramovic’s profits. Morgan’s script states ‘thirty million dollars’ as the floor figure for his payment, but Goold cannily changes this to a percentage, demonstrating that this arrangement is ongoing and cannot easily be escaped.

At times, Boris carries his vast wealth and power lightly, yet he also dictates the rhythm of every conversation he is in with stunning authority. That is, until he doesn’t anymore. In a meeting with then-incipient oligarch Abramovic, Berezovsky insists on keeping jazz piano live in the background. ‘It soothes me’, he says, though it quietly irks his associate. Yet when Abramovic demands greater clarity in their financial relationship, Boris slams the piano lid shut – intimidatingly yelling at the pianist ‘SILENCE!! WHAT IS THIS IMBELIC TINKERING?! IT TORMENTS ME!!’ The message is clear: like the piano music itself, Boris can be a soothing presence, opening doors, providing a roof and making you rich, but he can also be a formidable tormentor. He will allow you to be rich, but your money is made only by his grace.

Yet this arrangement will be mirrored in Putin’s Russia, where oligarchs’ activities and interests are permitted at the leader’s behest. Will Keen completing the leading trio well, playing Russia’s future ruler as a bureaucratic presence, stiff and drained of life – albeit with an undeniably vigorous work ethic, whose power, once attained, cannot be contested. He stands in the shame-riddled shadow of his military service in East Germany (where, Boris claims, ‘they generally sent the desk jockeys, the altar boys, the softies’). Berezovsky’s claim that not being selected as a real ‘KGB man of action’ attests to him ‘as a human being’, but the remark is barbed; Morgan notes that, here, Putin looks ‘eviscerated’. Berezovsky becomes too accustomed to this power play, seeing Putin as intrinsically weak and relatively low-status – even has he elevates him higher and higher, forgetting the potential risks. When Berezovsky helps Putin to get installed as Prime Minister of Russia, he assumes that he has attained political office himself. Yet Putin is no puppet. When Boris Yeltsin – perhaps the only man in Russia Boris cannot control, but only influence – names Putin as his successor as President (on the final day of the 20th century), Putin’s power comes close to absolute.

Berezovsky watches on in horror as his power runs dry. Hollander perfectly captures Boris’ initial denial, falteringly trying to tell Putin what he must do, but there is now no need for Putin to listen. His terrorising shouts only worked when backed up with real financial and political power. The man who, in Morgan’s telling, Boris near-singlehandedly groomed for puppet governance inevitably turns on his creator – a modern Frankenstein’s monster, who forces Berezovsky into exile in London. Berezovsky’s obsession with the infinite, the mathematical concept that so fascinated him as a child and which now functions as his prevailing ideology, has led him to overlook his finite, dwindling authority. One miscalculation is all it takes to undo him and those around him – such as personal bodyguard Alexander Litvinenko, known to his friends as Sasha, who was notoriously assassinated in London in 2006.

The play succeeds in exposing us to a story we might not otherwise know, or at least only know in part. The Almeida generally programmes shows late, allowing it to be more responsive than most theatres (both to world events and its high-calibre stars’ availability). Patriots was announced in May this year, and the play has inevitably existed long before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Yet, while the Donmar Warehouse’s meditation of the ethics of war in Max Webster’s Henry V seemed grimly serendipitous in its coincidental programming, Patriots feels far more deliberately placed. Thus, it works as something of a documentary play, a form of almost-journalism that seeks to inform us on a subject we should know more about.

Yet, Morgan’s drama never feels too urgent in its focus, particularly compared to the last major play to tackle Putin on a London stage. Lucy Prebble’s 2019 play A Very Expensive Poison, based on Luke Harding’s book of the same name and staged at the Old Vic, examined a similar subject by focusing on the murder of Berezovsky’s bodyguard, Alexander Litvinenko, who tried to raise the issue of FSB corruption with its then-leader, Putin. Prebble tackles Russia as a sprawling and rich culture, rather than Morgan’s simpler dichotomy of eastern, Siberian wastes and the cities of Moscow and St Petersburg, where political power is concentrated. While Morgan translates history to the stage with poise and wit, Patriots does not share Prebble’s ambition and flair. A Very Expensive Poison not only documents the story of Alexander Litvinenko, but it also searches for theatrical and real-world justice – honouring both his memory and the ongoing fight for the legal inquiry which his widow Marina Litvinenko lobbied for long after his death.

Marina appears in Patriots too as a character on the fringes. At first, she accorded a sense of power by Morgan – with Boris wooing her, rather than her husband, to leave the FSB and become his personal bodyguard. Yet she is treated more like a prop in the second half – telling Boris to settle down and find a wife, synthesising her (all too real) grief into a somewhat artificial call to action for the protagonist. In a fictional drama, we might not bat an eyelid, but it rings a little hollow considering the determined, passionate advocacy and activism of Marina, campaigning for the British government to take Sasha’s murder seriously. Here, she seems to have almost given up on life, telling Boris to save himself while he can, even if it is too late for her.

In A Very Expensive Poison, Prebble mounts a sustained assault on the fourth wall, its Vaudevillian stylings capturing the sheer theatre of Putin’s regime – with Reece Shearsmith’s Putin goading the audience, heckling from the private boxes, and even giving a talk about theatre itself. He casts himself as the master storyteller (and liar). Yet the play culminates in a powerfully emotional final puncture to the fourth wall, where MyAnna Buring’s Marina asked audience members ‘How do you do’ until all the artifice fell away. ‘I am obviously not Marina Litvinenko’, she says, before Sasha’s actual words are read out for us. Prebble indicts those who she considers culpable: not just the Kremlin and their Russian agents, but the British government response. Theresa May, Home Secretary before she was Prime Minister, is quoted – denying an inquiry into the murder due to ‘the cost to the public’ – a justification that three high court judges later found insufficient. Ignorance, Prebble argues, is too great a cost. Morgan is driven by a similar impulse, but it takes him a little less far, preferring character study to direct political statements.

Morgan’s drama mostly addresses the question of how we got here, rather than where we can go next, but it still stands as a strong and compelling take on an underexplored subject, powered by a tremendous central performance. Rupert Goold’s pacy production delivers political thrills and at times some visceral chills, playing out on a fabulous set from Miriam Buether, drenched in Jack Knowles’ moodily red-tinged lighting.

Whether Morgan successfully captures Russia could be debated. A repeated monologue bookends the drama, in which Boris tells us that westerners ‘have no idea’ what Russia is like, listing items of clothing and food as symbolic of Russian life and culture. Yet Morgan’s gestures toward authenticity seem a little hollow. The mocking of London for being too ‘metropolitan’, for example, speaks in a cynical language familiar to contemporary British politics. The word is pejorative in current British media rather than Noughties Russia, replete with connotations of wealthy liberal hypocrisy and functioning as sweeping shorthand in the same way ‘North London’ and (the Almeida’s own borough) ‘Islington’ have done. Boris tells us that we consider Russia to be ‘a cold, bleak place, full of hardship and cruelty’, yet Patriots hardly disproves this, leaning into it at times. It is only despite (or perhaps because of) these difficulties that Russia is so loved and treasured as a home by people like Boris Berezovsky.

In fact, the effect of the opening monologue’s repetition – fashioned into a sort of fourth-wall breaking suicide note – seems unintentionally to affirm the play’s limitations. After two and a half hours, we are charged with the same ignorance we had at the start; it has apparently taught us nothing. Perhaps the implication is that our incomprehension is a condition of western-ness, not a lack of knowledge per se. Yet on the page, Morgan’s intentions for the scene seem clearer. He asks that the sound of Vladimir Vysotsky’s ‘unmistakable’ singing voice be heard, while street vendors sell pelmenyi dumplings, a visible mirage of Boris’ nostalgia – nostalgia in its most literal, etymological sense: homesickness. This speech is summoning into being the Russia that he loves, so that – in his mind at least – he can die there, rather than in a perpetual exile. Goold, however, opts to play the scene straight, without manifesting Russia before us so literally. It is a very understandable impulse of restraint here; the mental image Morgan generates likely outshines the stage action that would be possible. It feels like not much has replaced these stage directions though, giving us the sense that little has changed over the course of the play.

Ultimately, as the title suggests, the major theme of Morgan’s drama is patriotism. It is a theme that quietly underpins most of his work, given his recurring interest in the British Royal Family, most notably. His last play, The Audience (staged in the West End in 2013), examines this through the contrastingly patriotic roles of monarch and Prime Minister. Here, Morgan names his focus explicitly. As a western play looking in, you might expect it to have a greater focus on how patriotism (and nationalism) operates in British politics, though this never quite manifests beyond the occasional winking satire. (Lines about the follies of elected government generate even more knowing laughter than they usually might.) The battle for Russia’s power and its soul is not fought between patriotic true Russians and western interlopers, hellbent on bringing deregulated free-market capitalism to Russia, Morgan contends. Instead, the play depicts two opposing forms of sincere patriotism. Putin and Berezovsky’s respective motives are partly self-aggrandising, power- and money-driven, yet both consider themselves to be acting for the good of Russia. They consider themselves to be the bridge between the present and an illustrious future. Yet, tellingly, it is always the nation itself that is identified as the beneficiary of patriotic altruism, rather than its citizens themselves.

Morgan takes them mostly at face value, as earnest – if conniving – lovers of Russia. Boris pines for his home from his life of luxurious exile, and Putin refuses his entreaties to return to life a quiet (and probably not even affluent) life as a mathematics professor – motivated, it seems, by a conviction that he must protect Russia from his westernised economic and political pressure.

In the second half of the play, Putin instates Abramovic as the governor of (what The Guardian calls) ‘the frozen far-eastern province’ Chukotka, six thousand kilometres from Moscow. In a March 2022 feature for The New Yorker, Patrick Radden Keefe called the province ‘comically inhospitable’ – noting that its ‘winds are fierce enough to blow a grown dog off its feet.’ Abramovic ‘pumped plenty of his own money into the region’, Keefe writes, and Morgan dramatises as fact something that is widely believed to be true: that Abramovic was very much steered into this apparently thankless role by Putin’s guiding hand. (Catherine Belton particularly advances this view in her 2020 book Putin’s People.) Though Boris may have been Abramovic’s Krysha once, in contemporary Russia, Putin acts as Krysha to all of the oligarchs. They keep their wealth only because Putin permits. Yet the scene where Putin visits Chukotka seems redolent of Morgan’s main theme; the billionaire is not only being groomed for his loyalty, but Putin appears to be testing Abramovic’s patriotism. The poverty of Chukotka is still far preferable to a life in exile elsewhere.

This is the vision of patriotism that crystallises in the drama: the pain of separation as greater than any hardships that life may contain. Berezovsky would surrender his wealth to keep his home, and Putin leverages that power against him, as Berezovsky leveraged power against others and him. Yet it is almost a moment where a vital fault line of the play is exposed; how much of what we are witnessing is true? It is another perennial concern in Morgan’s writing, and he treads a line between dramatizing facts of historical record and inventing within plausible parameters. The play bears no caveats about its level of fictionality, nor any acknowledged sources; its content does not signal (as Prebble’s gloriously absurd touches did) where gaps have been creatively filled.

In the bid to dramatise these lacunae, some moments strike false notes. The opening scene is one such example. We hear that the nine-year-old Boris has solved the Kaliningrad Bridge Problem – a traditional problem (previously called the Seven Bridges of Königsberg) in which a city’s seven bridges, connecting its various islands, must all be crossed on a single route, crossing no bridge more than once. The play as performed (but not the script) describes the fact that Euler solved the puzzle in the negative – meaning that he proved it has no solution. Euler effectively devised a new branch of mathematics in the process, and now – for mathematicians familiar with such methods – it is not too difficult a problem to solve. Unless Euler were catastrophically wrong (which he was not), solving it in the positive would be impossible.

This could just be stage shorthand for mathematical genius that contains a fairly fundamental flaw, or perhaps this is a deliberate tell, a sign that the drama is an imperfect, inherently unreal rendering of a life. The gist is true; Boris was an ambitious, intelligent man, and so too would his childhood have been. Either way, Patriots demands our attention in sifting hard fact from elegant fiction. Are we to take the characters’ claims of patriotism on trust, or should our suspicions be raised throughout? It would benefit from a little more direct admission of its inventions, but maybe fiction is what we are supposed to expect.

Patriots

Written by Peter Morgan, Directed by Rupert Goold, Set Design by Miriam Buether, Costume Design by Deborah Andrews and Miriam Buether, Lighting Design by Jack Knowles, Sound Design and Composition by Adam Cork, Movement Direction by Polly Bennett, Casting Direction by Robert Sterne CDG, Voice Coaching by Joel Trill, Assistant Direction by Sophie Drake, Russia Consultant Yuri Goligorsky, Starring Matt Concannon, Stephen Fewell, Ronald Guttman, Aoife Hinds, Tom Hollander, Will Keen, Yolanda Kettle, Sean Kingsley, Paul Kynman, Jessica Temple, Luke Thallon, Jamael Westman

Production Photographs by Marc Brenner

Reviewed 8th July 2022